From New Dawn 165 (Nov-Dec 2017)

In 1960 a book appeared in France that triggered a kind of revolution. Not a political one, although one of the book’s authors had political ideas that slanted distinctly toward the right. It was more a revolution of the mind, of the imagination we might say, or even of reality itself. In the Paris of Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus, of existentialism, black polo necks, engagement and dreary “authenticity,” the book had the effect of a flying saucer landing at the Café Deux Magots, or of a cosmic wormhole opening in Saint-Germain-des-Prés. In the black and white world of “nausea” and the “absurd,” Marxism and social commitment, it seemed to explode with technicolour visions of a strange new world. Or perhaps a strange old one, a forgotten past that at the start of that most modern of decades, seemed poised to return to lead a new generation into a fantastic future.

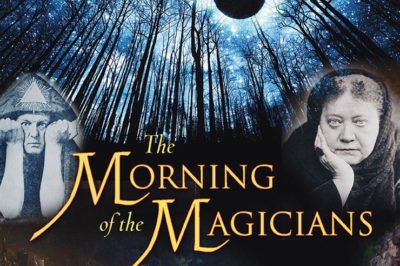

The book was Le Matin des magiciens, or as it was soon called in its American edition, The Morning of the Magicians (The Dawn of Magic in the UK). Its authors were an unlikely pair. Louis Pauwels was a journalist who had edited a hostile, misleading book about the enigmatic esoteric teacher G. I. Gurdjieff. Pauwels had spent his last years in Paris and edited the newspaper Combat after the end of World War II; a previous editor had been Camus himself. The Russian born Jacques Bergier was a physicist and chemical engineer with an interest in alchemy and a colourful past as a spy and resistance fighter. The two met while working on a series of articles on contemporary science for a popular Parisian journal. Accounts have it that they were introduced by André Breton, the Black Pope of Surrealism, who had a distinct interest in magic himself, as his exploration of the Tarot, Arcane 17, shows. If true, then the revolution sparked by his introduction proved more influential and widespread than the one Breton had hoped Surrealism itself would bring about.

Pauwels and Bergier soon discovered they had much in common. They shared a central insight, dissatisfaction with what they saw as the unnecessary limits of modern science, a constraint many find still in place today. Pauwels had already spent several years investigating various schools of ‘alternative thought’. Along with spending time in Gurdjieff’s groups in the late 1940s, he had also explored the teachings of Swami Vivekananda and the Traditionalism of René Guénon. Bergier too came from a somewhat mystical background; he often spoke of a great-uncle in Russia who had been known as a ‘miraculous rabbi’. Bergier had trained with the physicist André Helbronner, whose area of inquiry was the transmutation of elements, the essence of alchemy. Helbronner was murdered by the Nazis at Buchenwald and Bergier himself spent time in Mauthausen. After his release, he became a spy for the Allies. On one mission he discovered that the Germans had a secret supply of uranium, evidence, it seemed, the Nazis were close to making their own atomic bomb.

Bergier also claimed that in 1937 he met the elusive Fulcanelli, one of the most mysterious figures in the history of alchemy. Fulcanelli was believed to have discovered the secret of the philosopher’s stone and in his work Le Mystère des Cathédrales he revealed the hidden meanings of the alchemical “green language,” the esoteric symbols carved in stone in the great Gothic masterpieces of Chartres and Notre Dame de Paris. (Another said to have known Fulcanelli was the maverick Egyptologist René Schwaller de Lubicz, who claimed Fulcanelli stole the manuscript of Le Mystère des Cathédrales from him.) In the 1950s, Bergier’s name was linked to the American weird fiction writer H. P. Lovecraft, who had acquired a critical cachet in France denied him in his homeland. His fascination with Lovecraft’s work was long-lived. A letter Bergier wrote praising Lovecraft’s work was published in Weird Tales in 1936; another letter was published a year and a half later, lamenting Lovecraft’s death in 1937.

Pauwels and Bergier decided to write a book, exploring their ideas. For five years they gathered material, haunting libraries and periodical rooms, rummaging through newspapers, magazines, and scientific journals, seeking out curious and little-known bookshops. They studied ancient texts, investigated abandoned practices, and pored over reports of strange phenomena that were overlooked or actively ignored by the mainstream, creating their own kind of ‘X-Files’. They aimed to show how practices like alchemy, long dismissed by the modern mind, had many parallels with modern physics, and that in some strange way the modern age fast coming upon us might have more to do with ancient insights found in magic and the occult than we would suspect. In a way, they wanted to do for the post-war world what Madame Blavatsky had done a century earlier with her unwieldy masterpiece Isis Unveiled (1877): bring science up to date with the latest secrets from the remote past. This was in line with their belief that, “As a preliminary to understanding the present one must be capable of projecting one’s intelligence far into the past and far into the future.”1

Their publisher, Éditions Gallimard, assumed the book would have modest success. They were unprepared for the reception it received. France had a long history of interest in the occult – Gurdjieff himself had died only a decade earlier – but in 1960, angst was still the rage, and the bleak milieu of Waiting for Godot, with its grim comic nihilism, was still au courant. That a book on magic and alternate realities would set the Seine on fire was hardly to be expected. Yet, within weeks of publication, Le Matin des magiciens had both banks of the river talking about things that left existentialists scratching their heads. While Allen Ginsberg howled in the Beat Hotel and American tourists slipped editions of the scandalous Olympia Press into their suitcases, amazed readers of Pauwels and Bergier were talking about alchemy, spacemen, lost civilisations, magic, occultism, quantum physics, secret societies, altered states of consciousness, the weird discoveries of Charles Fort, forgotten groups like the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, and its once notorious members, like the dark magician Aleister Crowley and much, much more.

Kick-Starting the “Occult Revival of the 1960s”

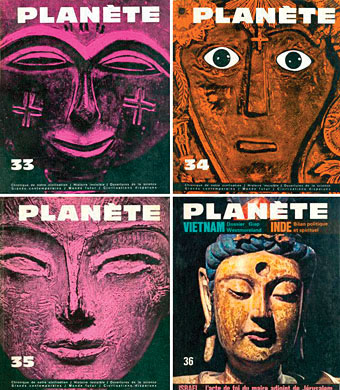

The book was a hit. It seemed to appear at just the right time and took everyone by storm. In the process, it kick-started what became known as the “occult revival of the 1960s,” ushering in an occult boom that lasted into the 1970s and remains with us today as the New Age. Les Matin des magiciens went on to sell millions of copies in France, and by 1963 there were UK and US editions, which did just as well. The long post-war drabness and futility had lifted and a bright, exciting, and marvellous future, filled with mystery and miracle, seemed to beckon. The book’s basic message, that there are more things in heaven and earth than are dreamed of by rive gauche philosophers, caught on. Paris-Presse called it, “One of the most exciting books of our time.” Le Monde devoted two long articles to its success, and that of Planète, the magazine that Pauwels and Bergier quickly started in magiciens wake. No longer were we stuck in our ‘historical moment’, as existentialists had said. The readers of Planète found that for 5.50 francs – not cheap at the time – they could investigate the ancient past, stretch their minds into the far-flung future, dive deep into their own inner worlds, or journey out into the stars.

Many Frenchmen did. At its height, Planète had a bi-monthly circulation of more than 100,000, an impressive showing for a journal of its kind. Although it did not translate into the English-speaking world as had Les Matin des magiciens, Planète was a success in Italy, Belgium, Switzerland, and conferences devoted to its themes were held in places as far-flung as Canada and Argentina. Buenos Aires was home to the writer Jorge Luis Borges, who shared Pauwels and Bergier’s taste for what they called “fantastic realism”; his work appeared in several issues and he participated in the conference held there.

Along with Borges, Planète’s pages were home to other writers well-known to European readers, such as the ufologist Aimé Michel, the science fiction writer George Langelann – whose story ‘The Fly’ was the basis for several films – and the cryptozoologist Bernard Heuvelmans, among many others. Articles ranged from “A New Science of Dreams” and “Korzybski and General Semantics,” to “The True Woman of the Thousand and One Nights” and “A Mutant of the Eighteenth Century,” with reprints of works by C. S. Lewis, the Austrian occult novelist Gustav Meyrink, Salvador Dali, and others.

With its wide range of subjects and eclectic editorial brief – “Nothing that’s strange is foreign to us” was its motto – Planète catered to the burgeoning taste for the new, the marvellous, the unusual and magical that characterised the decade of the “mystic Sixties,” with articles on science, literature, archaeology, film, history, occultism, and much else. Workshops and clubs based on Planète’s themes were opened in Egypt, India, and Mexico. Its reach was global, we could even say planetary, and its impact was, like that of the book that spawned it, eventually felt around the world.

Reality is Much More Fantastic Than We Imagine

The 1950s had seen some other odd best-sellers. Immanuel Velikovsky’s Worlds in Collision, for example, published in 1950,hadrevived the catastrophe theory of cosmology by arguing that a comet sprung from Jupiter just missed Earth but destroyed Atlantis and caused several biblical miracles as it passed by. It sold millions of copies. In 1956 the Englishman Cyril Henry Hoskins started a long and successful career with his book The Third Eye: The Autobiography of a Tibetan Lama, written under the pseudonym T. Lobsang Rampa. That Hoskins, a plumber, had never journeyed far from his home in Devon, England, seemed no obstacle to this account of his past life in the Himalayas, and his millions of readers agreed.

But The Morning of the Magicians – the edition I knew – was different than these and other popular books about flying saucers, like George Adamski’s Flying Saucers Have Landed (1953) or suburban witchcraft, like Gerald Gardner’s Witchcraft Today (1954). It tried to link together, however loosely, a variety of unusual phenomena and ideas, in most cases with little more than their sheer strangeness. It argued a point of view, the idea that reality is already much more fantastic than we imagine, and that if we peek beneath its surface, we will discover the strange connections linking everything together. This may be the roots of a ‘conspiracy consciousness’, but it is also the beginning of a sense of a deeper meaning, hidden somewhere within the everyday world, that we can discover if we look for it.

Where Lovecraft, a familiar figure to Planète readers, warns us not to connect the dots, for fear of discovering a maddening reality – “the most merciful thing in the world,” he tells us, “is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents.” Pauwels and Bergier positively insist that we do so. For them, reality is not devastating, but fantastic, and their pursuit of it is not an escape from life – as it is for many romantics – but a deeper participation in it. The fantastic was reached by making contact with reality directly, by throwing off old habits of mind and prejudices of thought and opening consciousness to new possibilities. It was reached through what Pauwels and Bergier, borrowing from Gurdjieff, called “the awakened state,” a new way of understanding reality, beyond the usual limits of “yes” or “no” that keep us hypnotised.2

It was this aspect of the book that attracted the praise of important figures like the philosopher Edgar Morin and the writer Umberto Eco. For the historian of religion Mircea Eliade, what was “new and exhilarating” about The Morning of the Magicians, “was the optimistic and holistic outlook… in which human life again became meaningful and promised an endless perfectibility.” We were called to “conquer the physical universe and to unravel the other, enigmatic universes revealed by occultists and gnostics.”3 Not all shared Eliade’s appreciation. Some, like the scholar of esotericism Antoine Faivre, who knew Pauwels and Bergier, saw the book as little more than a “masterpiece of confusionism” and “an adroit commercial undertaking.”4 That it was a commercial success is undoubted, yet an honest appraisal must admit to some “confusionism” as well.

An attentive reader soon encounters it. The book is full of inaccuracies, its breathless prose often trips over itself with sensational claims, its research is questionable, and references are at a premium. It is, as Colin Wilson wrote, a “curious hodgepodge of a book,” “too wild and undisciplined,” and lacking a connecting thread linking together its ideas about a hollow earth, ancient astronauts, lost civilisations and dozens of other strange items.5 In this, it suffers the same defect as the books of Charles Fort, a central influence on Pauwels and Bergier, and which also hampers their later collaborations Eternal Man (1972) and Impossible Possibilities (1974), neither of which have the same magic as their first effort. Blavatsky’s Isis Unveiled, mentioned earlier, has the same problem: it presents an enormous amount of material which, while undoubtedly startling and exciting, soon begins to numb through sheer excess.

Probably the most serious inaccuracies in the book involve the alleged occult interests of Hitler and the Nazis, dubious claims about dark forces at work behind the Fuehrer that have gone on to spawn a whole genre of suspect literature, and which seeped into music, film and other areas of culture. Serious investigations into the “occult roots of National Socialism” done by Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke, Hans Thomas Hakl and others throw doubt on most of the claims made about “occult Nazism” in The Morning of the Magicians.

There are other mistakes – those about the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn deserve special mention – but the general shakiness of many of Pauwels and Bergier’s claims has led the book to be categorised by later readers as a “grab-bag of inspiring misinformation.” In this it is much like the work of an earlier Frenchman with a taste for the occult, Éliphas Lévi, whose gripping and highly readable books on Kabbalah and magic, while inspiring many young occultists – myself included – are nevertheless peppered with mistakes and outright howlers.

Yet in one sense the sensationalism and inaccuracies of The Morning of the Magicians hardly matter; in the occult genre, sadly, they are often the norm. Whatever the book’s flaws, its place in the counter-history of western consciousness is secure. As I say in Turn Off Your Mind, my history of the influence of occult ideas on the 1960s, one of the remarkable things about The Morning of the Magicians is that it seemed to presage many of the themes that would come to dominate that decade.6 For one thing, it heralded the ancient astronaut craze that hit the screen with Stanley Kubrick’s psychedelic ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’ (1968) and made Erich von Däniken, author of Chariots of the Gods (1969),a rich man. But perhaps even more significant was its anticipation of the youth rebellion that would characterise the times.

One of the central themes of The Morning of the Magicians is that of the mutant, young individuals with strange abilities, who are evolving into a higher type of human, and who stand out from the average. Pauwels and Bergier give many examples of this phenomenon, but they were not alone. Around the same time ‘The Village of the Damned’ (1960), the film version of John Wyndham’s novel The Midwich Cuckoos, was released. It tells the story of a strange meteor shower that leaves the young women of a small English village pregnant, although many are virgins. The children turn out to be part of a collective mind, possessing enormous intellects and strange mental powers. And in 1963 Marvel Comics started what was to become one of its most successful series, The X-Men. This featured teenagers who, like the mutants of ‘The Village of the Damned’, possess weird powers and band together for support in a world that won’t accept them.

Not long after this, other, real-life teenagers felt something similar. In Haight-Ashbury in 1967 the San Francisco Oracle, the psychedelic spreadsheet for the Aquarian Age, published a “Manifesto for Mutants.” It proclaimed:

Mutants! Know now that you exist!

They have hid you in cities

And clothed you in fools clothes

Know now that you are free.

By then the occult revival, spawned by The Morning of the Magicians, was in full swing. The fantastic realism that its authors sought to awaken in their readers seemed, at least for a time, to have taken to the streets. If the ‘reality revolution’ of that mystic decade eventually petered out – Planète itself stopped publishing in 1972, Bergier died in 1978 and Pauwels in 1997 – the light of that magical morning nevertheless still shines today.

Footnotes

1. Louis Pauwels and Jacques Bergier, The Morning of the Magicians, Dorset Press, 1988, vii

2. Ibid., 96

3. Mircea Eliade, Occultism, Witchcraft, and Cultural Fashion, University of Chicago Press, 1976, 10

4. Antoine Faivre, Access to Western Esotericism, SUNY Press, 1996, 104

5. Colin Wilson, The Supernatural, Carrol & Graf, 1991, 1-2

6. Gary Lachman, Turn Off Your Mind: The Mystic Sixties and the Dark Side of the Age of Aquarius, Disinformation Books, 2003, 19; expanded UK edition The Dedalus Book of the 1960s; Turn Off Your Mind, Dedalus Books, 2009

© New Dawn Magazine and the respective author.

For our reproduction notice, click here.